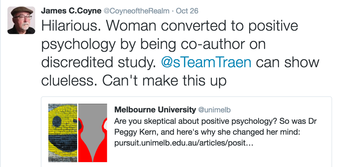

I'm not at all savvy with social media, but a few comments were brought to my attention, so I'd like to provide a few thoughts here. First, a comment by Jim Coyne:

For the record, I was not converted to pos psych. My research all through grad school focused on healthy aging and longevity (my masters thesis was about defining and measuring healthy aging) - who does well in life as they age. This could be called a pos psych perspective, but I was trained in health psych, rather skeptical of the whole pos psych area. I have come to see how my research interests all along align with the positive perspective, but that more comes from how my career has unfolded, more so than anything else. And it certainly wasn't from the Twitter study.

Work across multiple fields existed long before pos psych became an official field. Indeed, Abraham Maslow included the words "positive psychology" as a chapter in a book that he wrote in the 1950s. All through the 1900s, researchers studied exceptional lives. For years, developmental psychologists have studied optimal development - those who thrive versus those who languish, and the conditions and characteristics that distinguish the two. Health psychologists and gerontologists have considered quality of life, successful aging, and more. As pos psych took off, little credit was given to all of the work that occurred across the 20th century. Specific names are held up as the founders of pos psych. Yet these "founders" gave little credit to so much work that had already occurred. The field would benefit from shining the light more on the history and work that has happened for decades across diverse fields, rather than giving all credit to a few individuals (not to discredit the work they have done and the ways they have moved things forward, for better or for worse - just my two cents on things).

After grad school, I ended up with a postdoc position at the University of Pennsylvania, working directly under Martin Seligman and Angela Duckworth. I found myself increasingly a part of the pos psych world. That opened up a lot of opportunities for me, and also provided me with perspective, most of which I am not comfortable sharing publically. I can see plusses and minuses of the pos psych perspective. There is a lot of crap, with people over claiming things, practice running far ahead of the science, and what I find to be a strange tendency of people to use it all for personal gain. This makes me and many others hesitant to associate with it all. Be critical of all you read. Yet there is also some really good work occurring, often by people who refuse to call themselves positive psychologists. This gives me a sense of hope, and makes me want to be a part of it all. And in some of my work in schools and other places, I can see the personal impact that some of this can have - in ways that research has not found a way to capture. That makes it worthwhile to me to be a part of. But there are a lot of unknowns, and we ought to proceed cautiously.

The Pursuit piece then turned to work by the WWBP, like our study on Twitter and heart disease. Here are some comments:

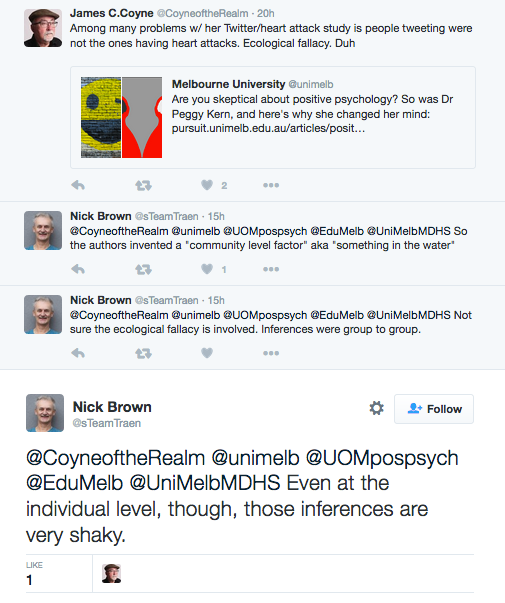

As we considered the results and tried to make sense of things, I put forth the argument that the tweets are revealing something about the community, which perhaps we can learn from. We included this in the paper as a possible explanation. Perhaps we can use this as a way to identify hot spots of increased risk, but then we need other methods to go into the community and find out what's going on - what's impacting the tone of the tweets and what makes it a high risk community. Nick Brown noted that we "invented a community level factor". Maybe we did. The explanation is simply one theory, and other theories are just as possible. We can't get to the explanation from the big data alone.

I see the Twitter study as descriptive in nature. Computer science likes to move that towards prediction, which is thought of in a different manner than by psychology, causing further misunderstandings. We found that using Twitter language, we out predict common demographic factors. This is a statistical way of looking at how accurately we could classify data, and creates some interesting graphics, which we create explanations about. But that doesn't mean we'd get the same results on a new set of data, and tells us nothing about why we see this. There are tons of explanations. So in the paper we put forth some ideas, building on other studies to support our arguments. But those might all be wrong. It concerns me that people want to rush on from this work and others and create algorithms and more - this goes well beyond what we did in our research, and I think is a misguided application.

Brown also noted that even at the individual level, inferences are shaky. This is true. People are complex. While we find "evidence" for things, effect sizes are moderate at best. There is a lot of person to person variation. I disdain blogposts talking about "10 proven ways to happiness". We don't prove things in psychology. We find support for an idea, with many other possible explanations. And often these are based on a handful of crappy studies on a limited sample. Just because there was statistical significance in a controlled study does not mean it will universally work for different people from different backgrounds. We need much more complexity. These are ideas that we are wrestling with at the Centre for Positive Psychology, in our work on positive systems science.

Science is a process. We put forth findings from a study, a possible explanation, some literature to support that. But we are influenced by our own backgrounds, world views, perspectives, and more. We try things out, get things wrong. Others try out the same study in a slightly different way, and results don't replicate. So we refine our thinking. Over time, we evolve our theories, studies, and thinking, getting closer to understanding how things work. But too often, researchers move right on to either the next best thing, or over claim what the results mean. So take the results of our study, and try to replicate it. Give another explanation of the results we found, then let's test it out. Correct our inaccuracies. And through that we can get to a better understanding of everything. That's how science is supposed to work.

So where does this leave me? Going back to the title of the Pursuit article, what keeps me a part of this field is that I do believe pos psych is more than happiology. While there are the big names that promote things (often going well beyond the science itself), there is also a deeper level of work occurring, often by junior scholars who don't get the credit and recognition they deserve. They come from diverse fields and perspectives, are applying innovative methods, and asking deeper level questions. They refuse to make universal claims, and are thinking about mechanisms, moderators, bidirectional pathways, different perspective within a system, inter-relatedness, and other levels of complexity. I'd like to think I am a part of that work at a deeper level, but I recognize that as I learn to work and deal with being in the public eye, that complexity can be lost, and I can come across as being superficial. Please know that I share your concerns, and I appreciate those who help me see places I have overstepped my bounds.